Image: People’s History of UofT

“what [the university] promised … cannot be reached by its methods nor in its spirits.”

– Dennis Lee, “Getting to Rochdale” in Student Protest (1968)

For the past 5 years I have studied, worked and engaged in various struggles at the University of Toronto (UofT). The most gratifying moments have been when my academics and employment overlapped with my activism, which has contributed much more to my actual learning process.

Being a student only felt healthy and enjoyable when my work addressed questions that I was grappling with in my daily life. Because I was so invested in student organizing, a lot of my research and writing focused on the university. I wrote this post as a way to take stock and share my “university notebooks”.

As I write this, the UofT administration is threatening to make another round of severe cutbacks with a proposal to merge a number of programs into a School of Languages and Literatures and to simply eliminate others (including Diaspora and Transnational Studies, which I minored in). It’s all too familiar. The presentation of proposals as foregone conclusions. The duplicity: citing the “economic reality” while proposing to redirect the funds elsewhere. The shock and indignation of affected parties.

I feel an impulse to ask “Where were they when we were under attack?” Where were they when the Transitional Year Programme was threatened with closure, when Disability Studies was on the chopping block, when university workers were fighting for a fair contract? But this line of thinking only supports divide-and-conquer tactics. What delivered successes in all of the above cases was the power of solidarity. These moments are learning opportunities. They are yet another wake-up call to form a united movement in opposition to cuts and the corporate agenda of the university.

And if we’re fighting to “save the university”, we also need to consider exactly what we are attempting to save. Some of the first programs to be targeted are those with equity-seeking mandates. But these programs and ideas have always existed in a context of struggle. It is easy to dismiss the role of equity in the university as public relations, as strategic cover for the broader functions of the university, yet this erases the history-from-below, the struggles to make space for these programs and radical ideas in the first place.

The university remains an important site of resistance: of inquiry, debate, forming new relationships and communities, and fighting for justice. This work represents some of what I have learned about the university and student organizing. Of course, I am hugely indebted to everyone I have had the privilege of organizing with, because knowledge production is a collective process.

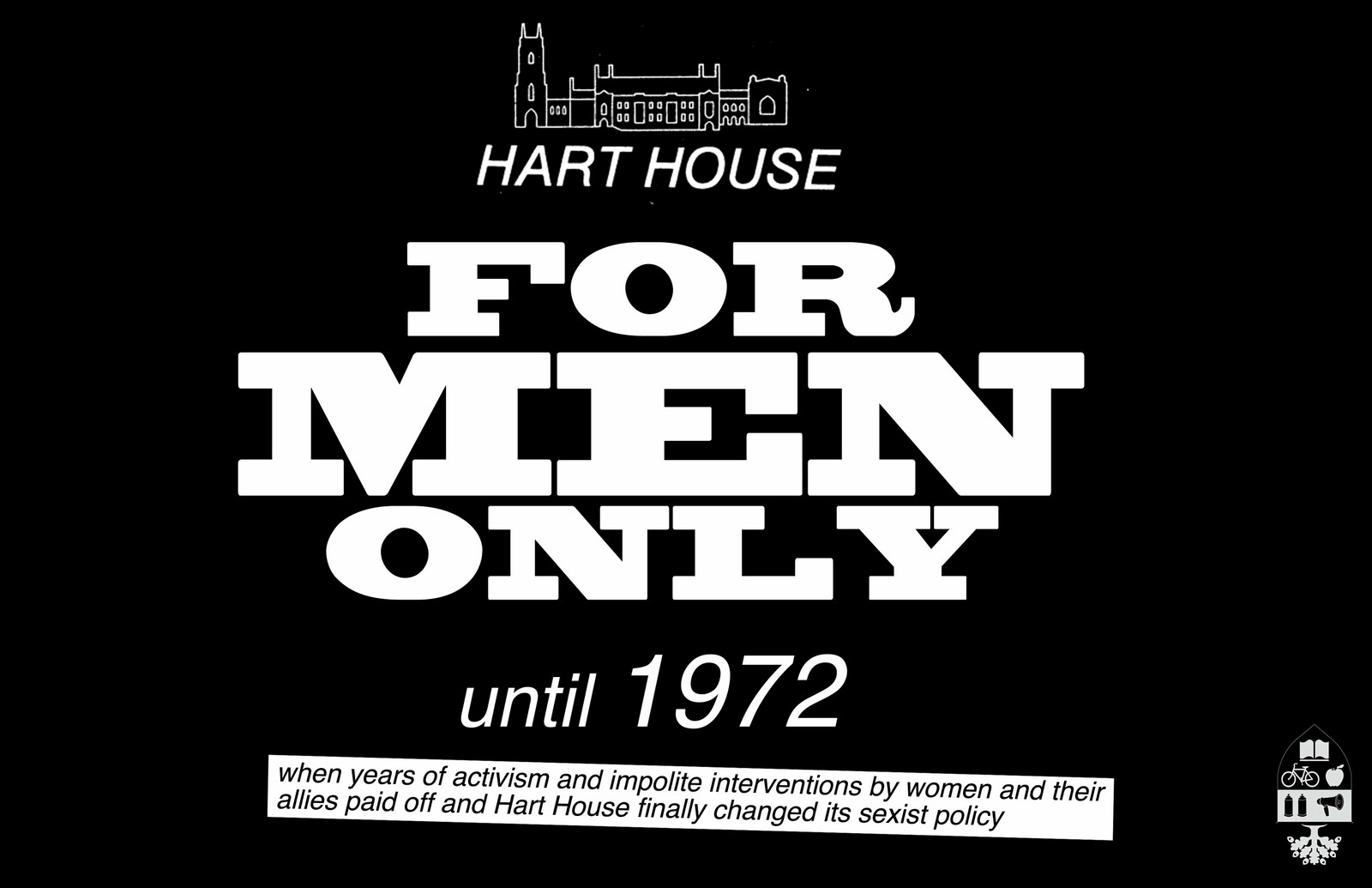

Images: People’s History of UofT

The University as a Space of Resistance (pdf)

Part manifesto, part history lesson, this is the first major student activism paper I wrote. I wanted to help people remember the forgotten history of radical activism at UofT, just as Gary Kinsman writes about the often forgotten radical roots of queer struggles, and put forward some radical ideas to move beyond the limitations of reduce tuition campaigns, token representation in university decision-making, and the dismissal of “non-student issues”.

I wrote about the university undergoing a process of privatization and about possibilities for resistance. I started with the idea of the right to education and the logical conclusion that education should be free – a conclusion supported by the folks who organized Free Education Week and a Free UofT that at one point offered over 50 courses. Next, I wrote about the right to education as not just the right to a seat in a classroom, but the right to actively participate in education, citing the powerful grassroots campaign for parity in university decision-making, the roots of course unions and course evaluations in student dissatisfaction, and the direct action tactics like sit-ins and occupations that students have historically had to engage in to make their voices heard. Finally, I discussed international solidarity efforts such as anti-war and divestment campaigns, where students have held universities accountable for their complicity in global injustices.

Unmapping the Corporate Campus: Cartography of a “Free University of Toronto” (pdf) (map)

The purpose of this project was to talk about “free education” as more than a demand – as something that students and their allies have been actively producing from the ground up.

Thinking about the courses and ethos offered by the people who organized Free UofT, I realized that there is already a surprising amount of infrastructure for a potential free university: student unions and labour unions with their own space and buildings, well-established housing and daycare cooperatives, student-run food operations, student-run newspapers, a campus radio station, an anti-oppression resource library, and student and worker-run organizations that collectively hold hundreds of lectures, events, and skill-building workshops each year.

These projects can (and many do) support each other and broader political organizing while serving as living examples of demands for a free and democratic university. To help illustrate this idea I produced a Google Map.

Racism and the University: How Bureaucracy and the “Equity Industry” Perpetuate Racism (pdf)

My approach is this paper was inspired by Rodney Bobiwash’s speech on the difference between “substantive equity” and the “equity industry”. Just as Bobiwash noted in 1998, the university is part of the “equity industry” and perpetuates systemic racism (among other forms of oppression).

This is part of a series where I focused on specific struggles – in this case anti-racist organizing by students in the late 1980s and present – and their impact in shaping the history of the university. While peddling his Towards 2030 plan, the university president was confronted by students due to the lack of an equity agenda and in particular over the university’s Eurocentric curriculum. When he responded that the issue was outside of his jurisdiction, he was reminded of the anti-racism report commissioned by the university president in 1992, which included a full section on curriculum, and of the recommendations that had largely been ignored.

I use this anecdote as an opportunity to look at the anti-racist activism in the late 1980s that was simply too strong for the university to ignore. The university’s response was to redirect the energy from activism into bureaucratic channels (like a presidential committee and report), to make small tweaks to insulate the university from calls for systemic change, and carry on with an agenda of corporatization. Present-day movements have learned by uniting equity issues with anti-fee and anti-corporatization organizing and by remaining skeptical of the university bureaucracy and equity industry.

Making Space for Access and Equity in the University: Lessons from the Transitional Year Programme (pdf)

By following the history of the Transitional Year Programme (TYP), a special access programme founded by members of the Black community in the summer of 1969, I was able to see the struggle to establish and secure a genuine access and equity initiative in the university, and how the presence of a community-centered initiative like TYP has enacted broader changes across the entire institution and continues to challenge dominant, exclusionary ideas about “excellence”. As TYP co-founder Horace Campbell has written, “Ultimately, the success of TYP should result in the removal of the need for TYP”.

I discuss threats in the present including the devaluation of equity (even in the token sense) by a new crop of senior administrators, however one thing I neglect to go in to is how the new “self-sufficiency” budget model is used as a battering ram to advance their corporate agenda.

Student Struggle / Student Rights: International Solidarity Campaigns and the Right to Education (pdf) (web)

This paper focused on divestment campaigns by students organizing around South Africa in the 1980s and Israel in the present.

The anti-apartheid campaign in the 1980s illustrated how divestment was not just a blow against the South African regime, but also a blow against the arrogant policies of the university administration that refused to meaningfully include student voices. Further, it is an instructive example of how direct action – in this case, students disrupting a meeting of the Governing Council and jumping on tables (after four years of inaction by the administration) – can take a campaign to the next level and achieve its objectives. The disruption of the meeting made the front pages of the Toronto Star and Globe and Mail, resulting in increased public pressure and, soon after, divestment.

Palestine solidarity work on campus exists today in a context where universities are increasingly aligned with private interests and have developed new methods of managing dissent, including Student Codes of Conduct, bureaucratic interference and hurdles, denial of space, and outright censorship. The lesson we can draw from both struggles is that the right to education resides in the collective power of students. Student rights are non-existent without demonstrable student power.

Neoliberalism and Citizenship: The Case of International and Non-Status Students in Canada (pdf)

One of the few times where I was able to connect student organizing with migrant justice organizing, this paper looks at the roots of differential fees for international students in neoliberal cutbacks to government grants, the increasing dependence of universities on international student tuition fees, and how this fee model has affected undocumented or non-status students. The fact that this growing dependence on international fees also affects “domestic” students, with targets for domestic students decreasing at UofT, allowed me to consider shifts in access to social goods like education from access based primarily on citizenship to access based on wealth (of course these are linked). I argue that neither is desirable and turn to activist struggles that fight for access for all community members regardless of wealth or citizenship status.

Image: People’s History of UofT

Over the past year I have worked with friends on taking these histories we have encountered and making them more accessible through posters like the ones posted here and on the People’s History of UofT blog.