In 1965 artists got their first major call to service when Cesar Chavez’s Farm Workers Association joined the Delano grape strike initiated by Filipino workers and became the United Farm Workers (UFW). An unprecedented number of urban Mexican Americans supported the strike, thus accelerating the transition of a labor movement into what became the Chicano civil rights movement. “It had a startling effect on the Mexican Americans in the cities; they began to rethink their self-definition as second-class citizens and to redefine themselves as Chicanos.”

– Tere Romo “Points of Convergences: The Iconography of the Chicano Poster” in Just Another Poster? Chicano Graphic Arts in California (2001) edited by Chon A. Noriega

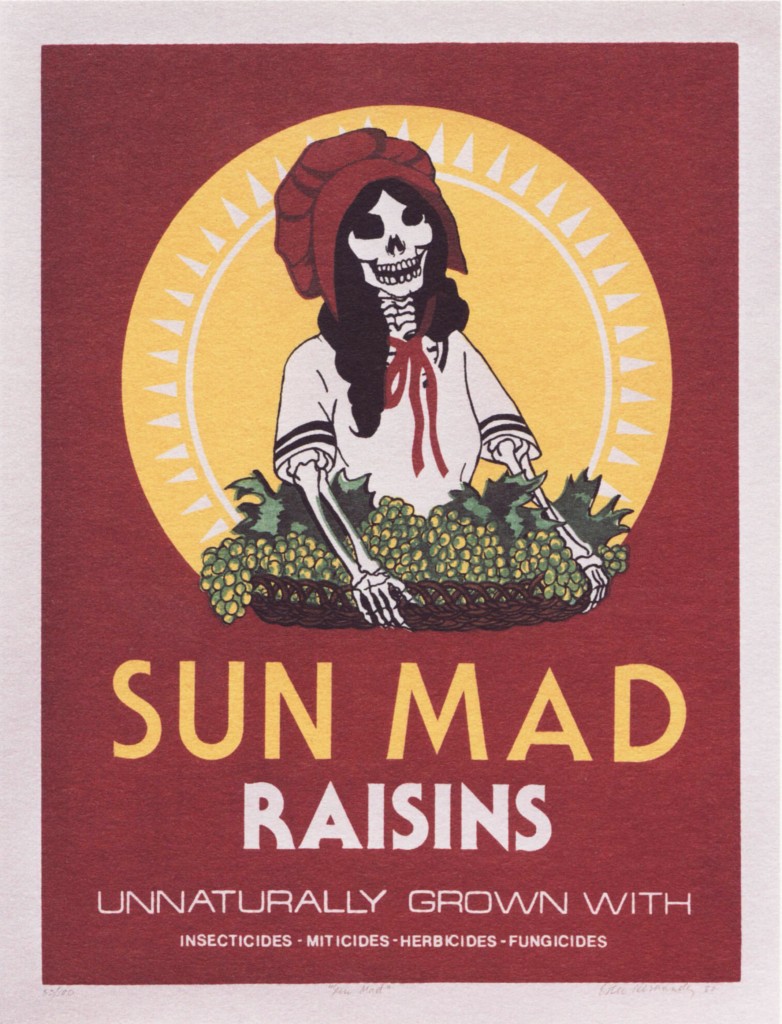

Sun Mad (1982), Ester Hernandez

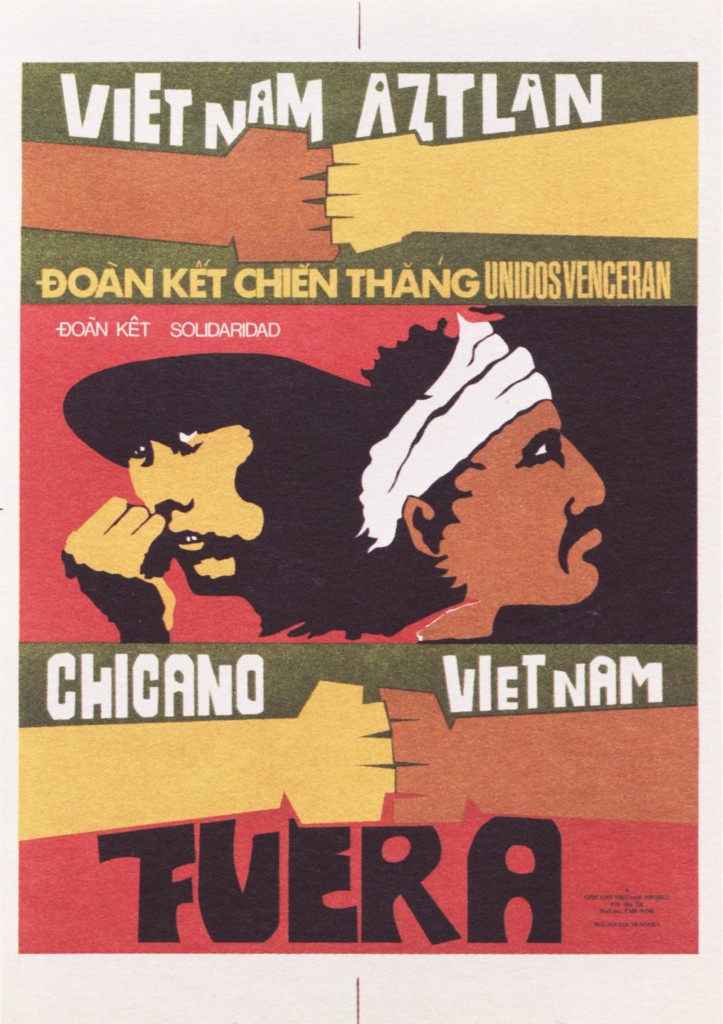

Within a Chicano context, the issue of belonging and ownership in relation to land is evoked through the idea “Aztlán”. Aztlán names the mythic homeland of the Aztecs before their migration to the high vallery of central Mexico. It was introduced to Chicano thought with “El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán”, drafted in March 1969 for the Chicano Youth Conference held in Denver, Colorado.

As a mythic homeland, Aztlán grants a prior claim to the land Chicanos occupy. This leads to the popular saying, “We didn’t the border. The border crossed us”.

– “Remapping Chicano Expressive Culture” by Rafael Pérez-Torres in Just Another Poster? Chicano Graphic Arts in California (2001) edited by Chon A. Noriega

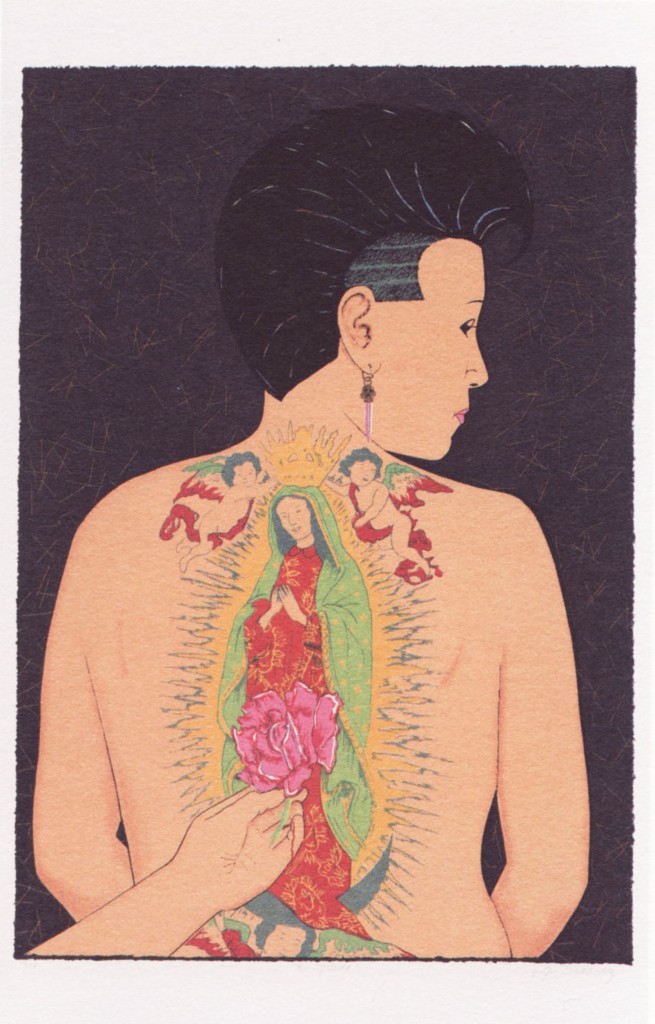

La Ofrenda (1988), Ester Hernandez

La Ofrenda (1988), Ester Hernandez

“… the idea of Aztlán allows one to form solidarity with a number of national and international social struggles for justice. Aztlán comes to represent on a symbolic level another type of reclamation, one underscored by the “queering” of iconic figures by de Batuc and Hernández. Morago writes, ‘For immigration and native alike, land is … the factories where we work, the water our children drink, and the housing project where we live. For women, lesbians, and gay men, land is that physical mass called our bodies. Throughout las Americas, all these ‘lands’ remain under occupation by an Anglo-centric, patriarchal, imperialist United States’.

Chicano expressive culture often relies on evoking the many meanings of land in order to grasp the numerous ways sociopolitical power and personal identity intersect. Chicano consciousness has emerged from the recognition that the circulation of power manifests itself in the circulation of the body through social institutions like school, prison, and the workplace.”

– “Remapping Chicano Expressive Culture” by Rafael Pérez-Torres in Just Another Poster?

Vietnam Atzlán (1973), Malaquias Montoya