Graffiti stencils in London, Ontario via Toban Black

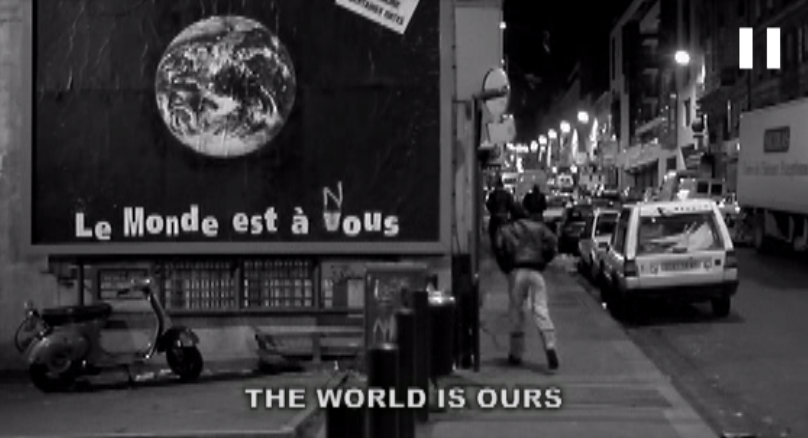

Playlist: Pledge of Allegiance / PJ Harvey “The Glorious Land”

On my first day of school, I remember being introduced to my teacher, Ms. Witch, dressed in all black. When music started playing from the ceiling and everyone froze, I was mystified. What sorcery was this?

Some of my teachers expected us to sing this song, or to faintly mouth the words, but we always had to observe the anthem obediently, if only in silence.

Hearing the music confirmed that you were late, that your body was not where it should be. Watchful figures guarding hallways stopped us in our tracks, holding us with their stares, adding to our delays, to make sure we observed the anthem.

Why was it so important to them? What did it mean?

For one thing, respecting the anthem is part of upholding respect for “the rules” and rulers who govern schools. Otherwise, anarchy would break out.

And then there’s the national part of the anthem. There’s a reason why they make 4-year-olds rise at attention and profess “true patriot love” before we even know what that means.

Playing the national anthem in schools is part of nation-building, or upholding respect for “the rules” and rulers who govern Canada.

***

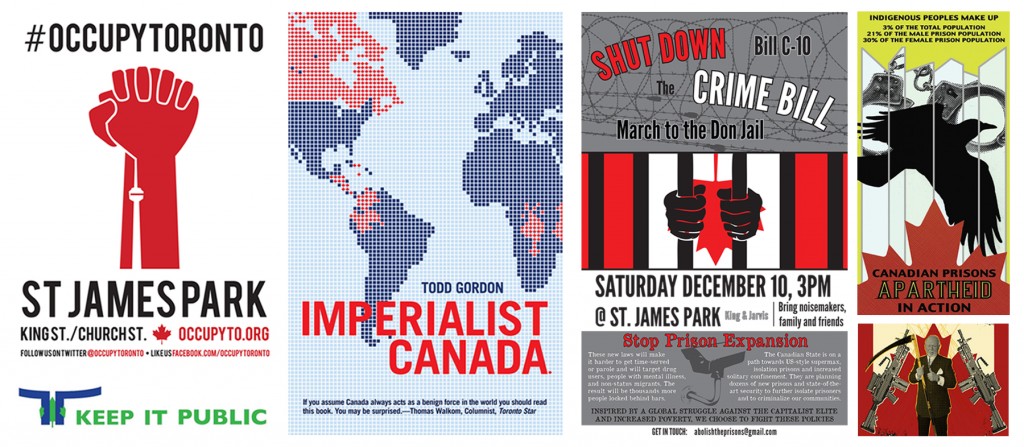

As activists and designers working with social movements, many of our struggles require us to challenge “the rules” and rulers who govern Canada.

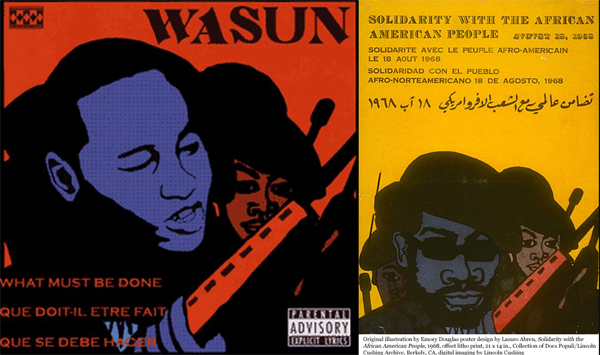

Switching formats from audio to visual, I’d like to look at a different nationalist symbol – the Canadian flag – and the way it gets used in graphic design.

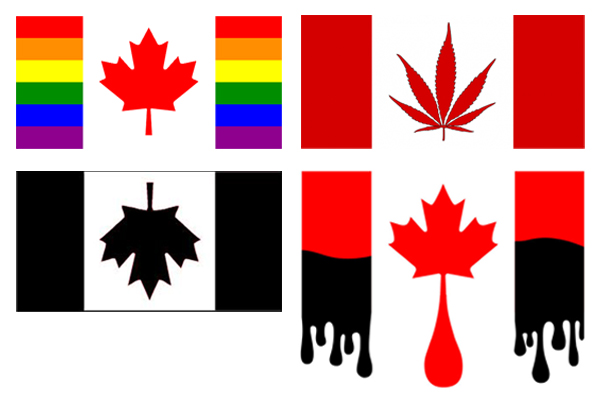

Flags: Rainbow, Marijuana, Black, Tar Sands

When I look at simple graphics that riff on the flag, I notice two kinds of dynamics: seeking inclusion by wrapping yourself or your subject in the flag; and raising critical ideas by showing the flag in a new light.

In the first pair of images (top left + right), the association with the flag is viewed as benign, while with the second pair (bottom left + right) the image of Canada is visibly tarnished.

However, all of these images share a common limitation. Not one grasps things at the root. How can we talk about nation-building without acknowledging the colonial history and present of Canada?

So-called “Native Canadian” flag, unknown origin; 2010 Canadian Olympic hockey jersey logo by Debra Sparrow (Musqueam) with Nike (not a flag, but may as well be one)

Even images that engage with (some might say co-opt) indigenous art and identity can fail to do this. Perhaps intended as an inclusive gesture, or as a powerful corrective, my concern is that this is actually a form of assimilation, of subsuming indigenous nations under Canada in order to extinguish land and treaty rights that are rooted in nation-to-nation relationships.

Ultimately, the Canadian flag is part of an ambitious re-branding exercise. The goal is to consolidate the emotional pull of nationalism to avoid the unsightly reality of Canada’s colonialism.

***

So just because you use the Canadian flag in your design, does that mean you are supporting colonialism?

Aren’t there good reasons to use the Canadian flag? The flag is an instantly recognizable symbol. It provides political and geographic specificity. It helps us name power so people can understand what we’re talking about.

Let’s look at some examples.

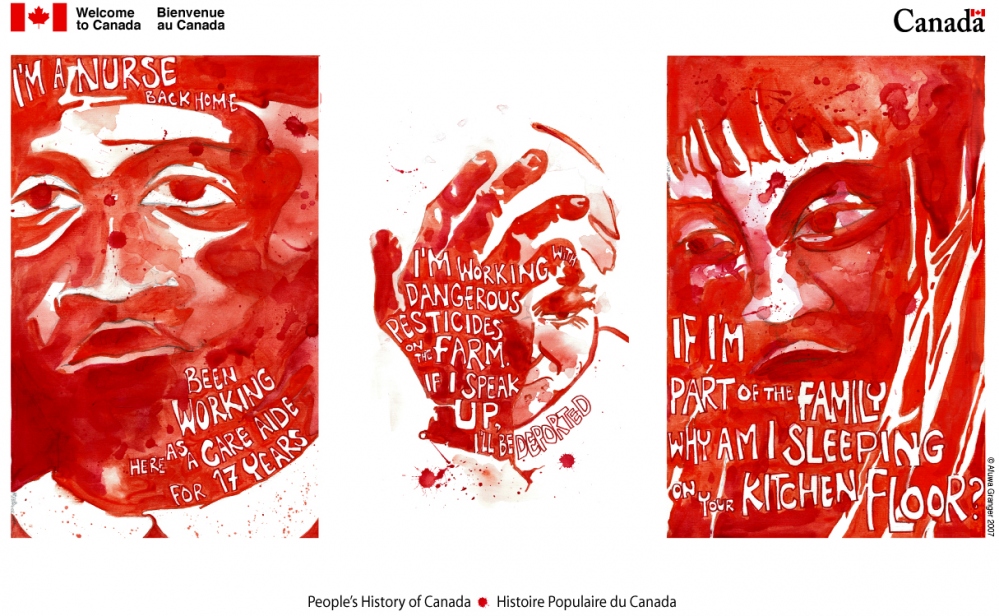

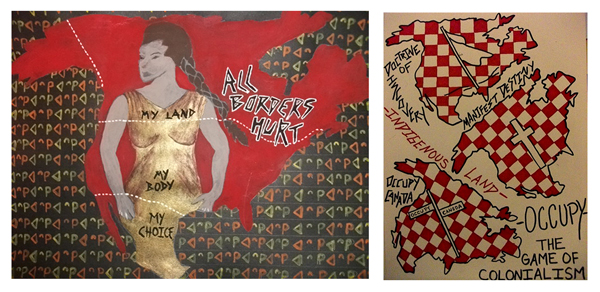

By Afuwa Granger as part of NOII-Van’s People’s History of Kanada Poster Project

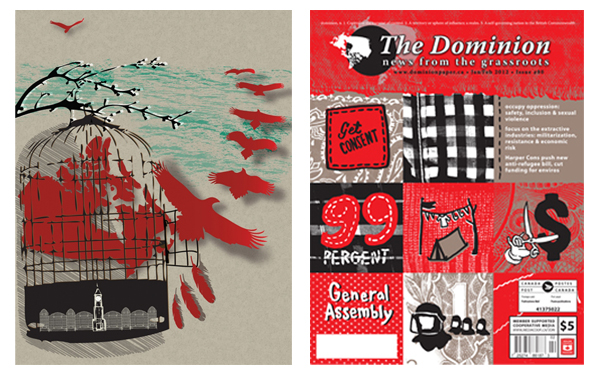

No Borders & Occupy: The Game of Colonialism by Erin Marie Konsmo, Métis/Cree Indigenous feminist and artist

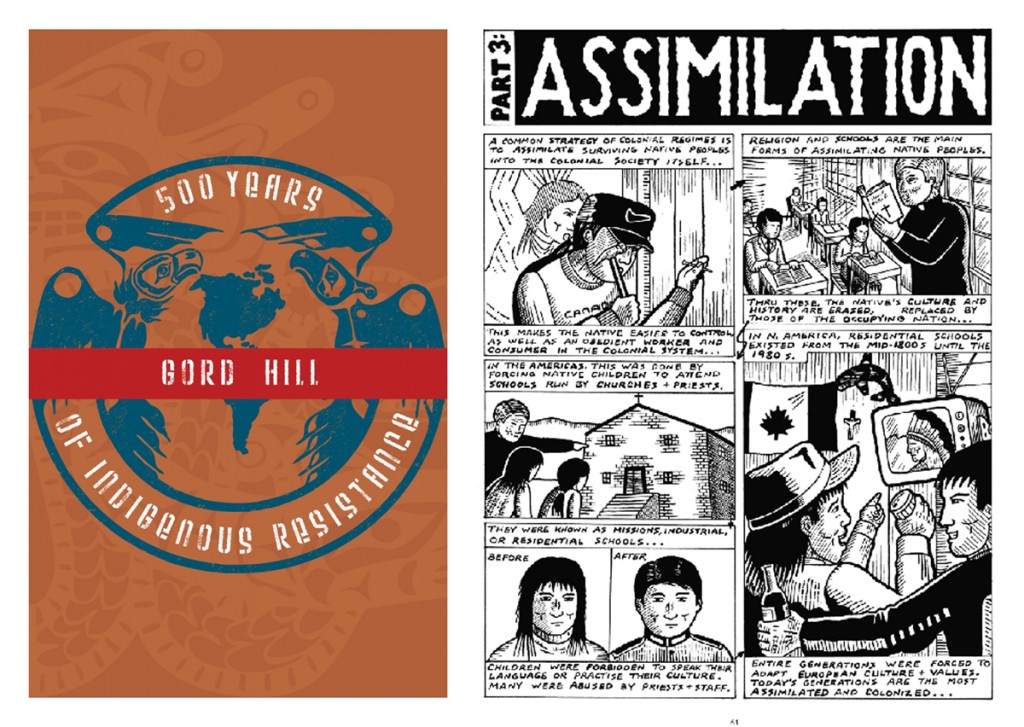

500 Years of Indigenous Resistance, cover and pg. 61, by Gord Hill, member of the Kwakwaka’wakw nation on the Northwest Coast

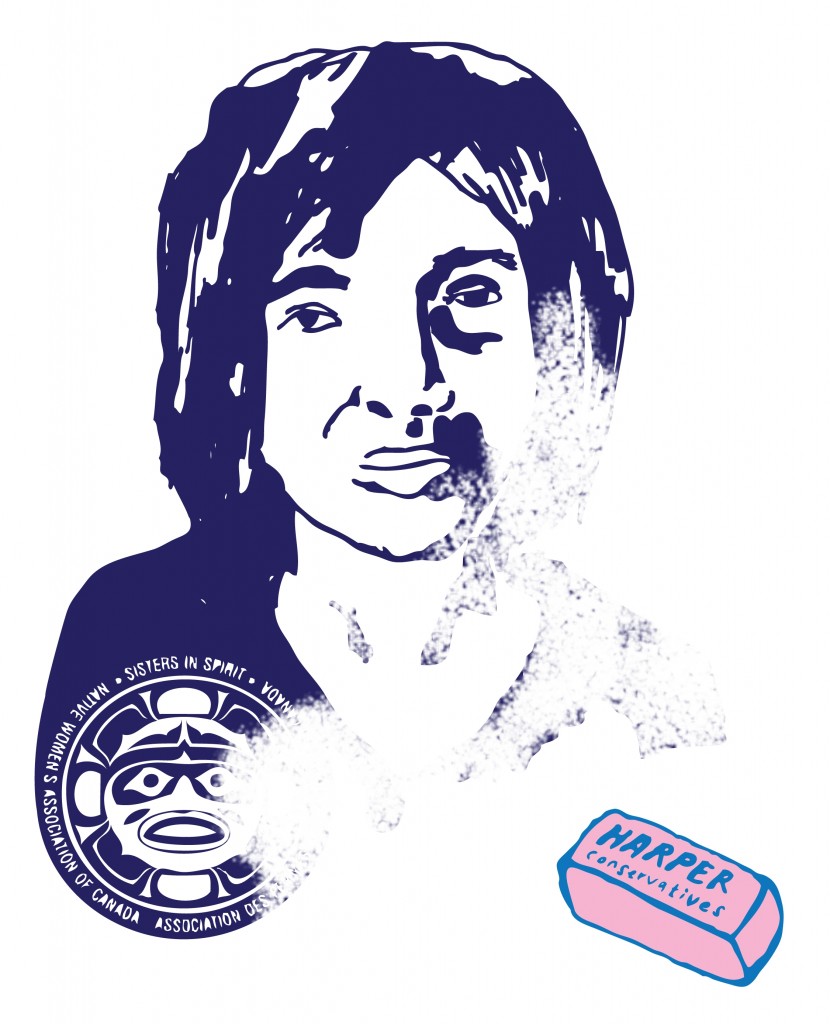

Illustration by Emily Davidson for The Dominion

3 thoughts on “Burning the Flag”

Great blog! I really enjoy your work !

Thanks Erin, your work is huge source of inspiration!

This is a really good piece of writing. The opening segment was brilliant