I’ve wanted to write something about this book since receiving it as a gift last year.

I first learned about Roadsworth and his imaginative street art from the Wooster blog. I saw traces of his work on visits to Montreal. The NFB produced a documentary about him called Crossing the Line (2008). And during the 2009 Manifesto festival he was commissioned to a do a piece outside the 52 McCaul gallery.

His story is pretty interesting and the book devotes a good amount of space to letting him tell it in his own words.

We begin with a guy who feels alienated and frustrated making the decision to produce a flurry of uncommissioned street art. His work catches the attention of a wide audience and later the police, leading to his eventual arrest. By this time he has created over 300 illegal pieces and his supporters launch a public campaign in his defence. At the end of a lengthy legal process, Roadsworth is given a sentence to do some community service by producing a mural with a local school. Meanwhile he is beginning to accept commissions for legal work — from the city, shopping malls, fancy fundraisers and international art events.

This story makes me think about success — success as an achievement and success as a modifier, a game-changer. What does winning look like? What happens when your light gets noticed, when you are being tracked, or when you receive offers of inclusion?

By definition, success can mean “accomplishment of an aim or purpose” as well as “attainment of popularity or profit”. Popularity or profit is socially coded as a default measure of success. When we look at accomplishment and attainment we tend to focus on the ends rather than the means. The other assumption, especially with art, is that success is “earned” by individuals, i.e. creative geniuses working in isolation.

Someone told me that Russell Brand once said “the world doesn’t need more successful people — we need more good people”. I couldn’t find that quote, but I did find this one:

“The plain fact is that the planet does not need more successful people. But it does desperately need more peacemakers, healers, restorers, storytellers, and lovers of every kind. It needs people who live well in their places. It needs people of moral courage willing to join the fight to make the world habitable and humane. And these qualities have little to do with success as we have defined it.”

— David Orr, Ecological Literacy

Let’s say we agree with Russell and David here: we need to re-define success, or to do away with the corrupted idea completely — if success is derived from succeed — “to come close after” — to do what is expected of you — that’s just encouraging mindless repetition and entitlement isn’t it?

In a VICE profile Japanese tattoo artist Horiyoshi III talks about the martial art concept of shuhari — a three-stage process that begins with learning a tradition from a master. In order to grow and evolve, you must break away as a step towards transcending your master. From there, you have to transcend yourself — Horiyoshi calls this the hardest stage and says that he still feels like he is in the midst of breaking away.

I’m not proposing that we appropriate this idea to found codified academies of creative resistance that will produce new masters of street art, I just wanted to offer an example where success is defined otherwise — not by attainment of popularity or profit — but by being rooted in a tradition (something bigger than yourself), ongoing learning, exchange, and self-reflexive growth.

Even though I really wanted to squeeze that example in, I’m wary of the idea of mastery. Mastery may offer a different spin on the meaning of personal success (what you do instead of what you have), but meritocracy doesn’t work as social policy — not when access to opportunities is still determined by systems set-up to reward privilege and punish difference.

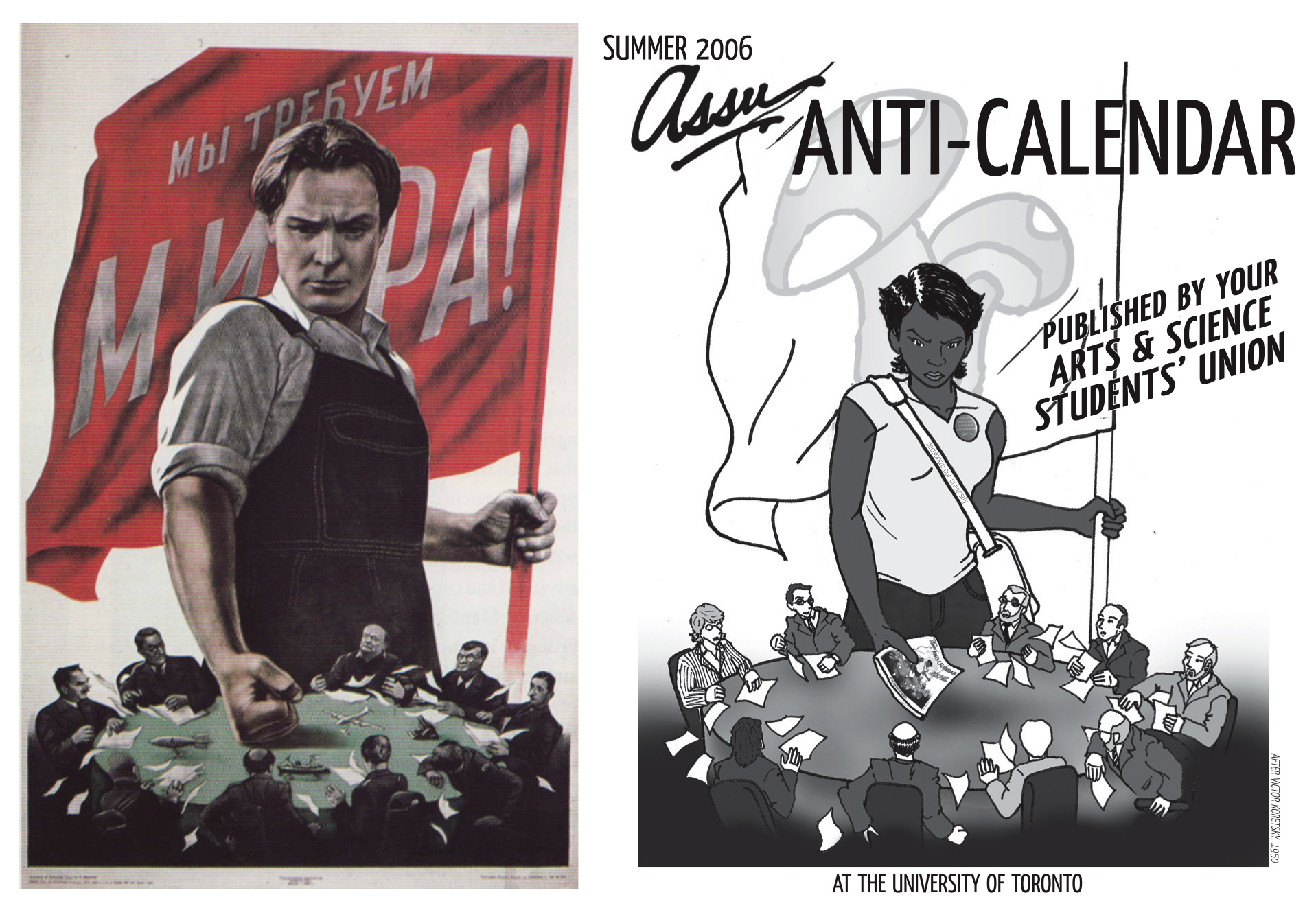

The master narrative of great artists isn’t a threat to hierarchical social relations — it fits the scheme perfectly. The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house right? But that’s where this book brought me — the rarefied air of material resources and mainstream visibility tentatively offered to a few successful artists — so I began thinking about how artists deal with the contradictions of success.

Three kinds of responses came to mind: redistribution, collaboration, and refusal.

Sometimes Banksy capitalizes on his marketability by offering a limited run of prints to raise money and awareness for political causes. The offering is like an event in itself.

Through the Yes Lab, the Yes Men collaborate with movements to plan creative actions that attract media attention to issues like the Tar Sands. Their infamy as pranksters can make their hoaxes more newsworthy and attract more support for fundraising efforts.

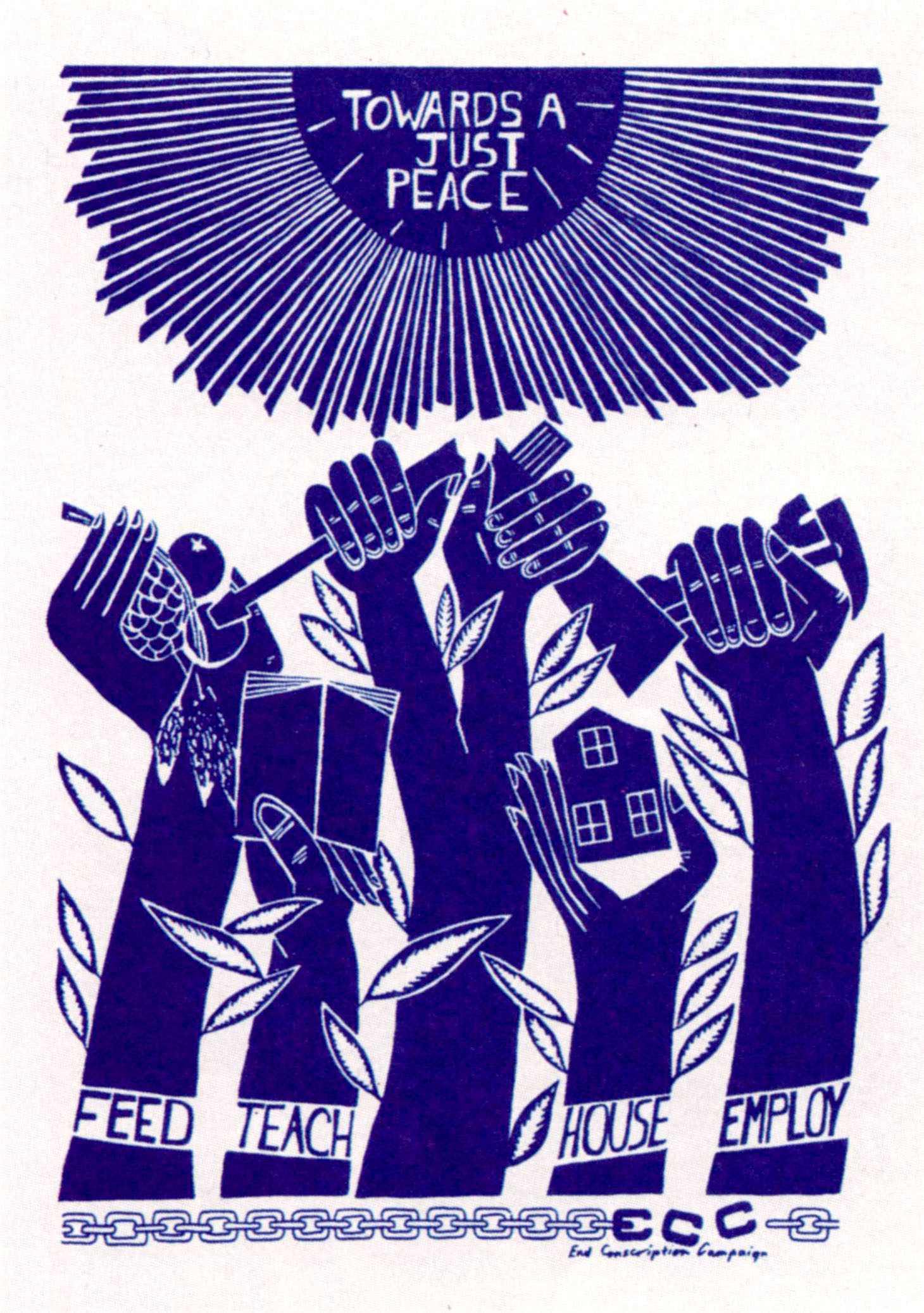

In the 1970s Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge were successful artists. After moving to New York from Toronto, they were invited back by the Art Gallery of Ontario for a retrospective show on their minimalist sculptures. Conde and Beveridge were politicized during their time New York and decided to turn the show on its head, using it as a launching pad for a new collaborative practice of politically-engaged art. Their decision resulted in them essentially being blacklisted by the gallery, but they have sustained their practice for over three decades and continue to work with union members, migrant farm workers, and other groups organizing for social justice.

My thoughts on success are still incomplete and there are definitely loose ends here.

Success isn’t just a thing that some possess and others lack — a 0 or 1, on/off — it’s a powerful, seductive idea that we all have a relationship to.

Here’s a Russell Brand quote that I can actually source — it’s from his Booky Wook 2 — about how we see famous people:

… like all objects of fetish, all icons, they are a reflection of your perception. They are used like saints or gods; here to tell stories, to give us warnings of the perils of success or to be held aloft as examples of contemporary ideals. One figure can be used to represent either extreme, depending on the culture’s mood; David Beckham or Lady Diana can be an example of domestic excellence or individual indulgence depending on the tabloid, depending on the day.

I was first hooked by the visuals in Roadsworth. Then it was the inspiring come-up story about Roadsworth winning popular support for his illegal art. But what stuck with me was the other success story — the engagement with paid legal gigs and how I felt the meaning and strength of the work changed in this new context.

It’s cruel to adore an artist when they’re hungry and begrudge them when they are able to pay their bills, I know that. And yet the dissatisfaction I felt was real — not just jealousy or self-assurance masked in holier-than-thou criticism. The for-hire work inevitably gets viewed in relation to all your other art. But to be fair, it also represents a new period of experimentation with the limitations and possibilities (like going bigger, taking your time) presented by doing sanctioned work — and because that type of work isn’t as direct, as unmediated — it may need to have different aims and purposes. And we may need to lower our expectations.

But what fun (or good) is that? There’s a silly book about Banksy out right now called You Are An Acceptable Level of Threat And If You Were Not You Would Know About It. I actually quite like the title — it’s something to think about with Banksy’s work — or Roadsworth’s — and of course our own as well. What is laughable is the back cover’s assertion that Banksy is the closest thing we have to a modern Che Guevera — which on second thought, may be true for pseudo-radical merchandising efforts.

I’m reminded of this quote from an interview with author Junot Diaz on his writing process:

If you are not lost, then you’re at a place someone has already found. I mean, If you feel familiar and you feel comfortable, you’re in mapped territory. What’s the use of being in mapped territory? If you’re going to spend x number of years in a book, you might as well be doing something new, and that requires you being completely lost.

Let’s get lost together, over and over again.